The New York Times has published an

article on the results of a study conducted out of Syracuse University that claims to have found a drop in the number of terrorism cases prosecuted in the USA since 2002. The stated causes are a lack of

evidence and other legal problems. Not taking at face value what one reads in the newspapers is prudent, particularly in light of recent plagarism, photoshopping, and other incidents, along with the (sometimes acknowledged, but often not) biases of the news media. However, that being said, there are likely some important truths buried in the study and article for those who care to dig for them.

One thing that came to mind while reading the article is that terrorism has created a dilemma for judicial, law enforcement and security agencies alike - how can we 'stop' terrorism? Can we treat it like a typical law enforcement function (i.e. wait until after the crime occurs, collect forensic evidence, investigate, and prosecute)? That fits in with our modern day western ideas of justice, but it means that innocent people die (I am using the term "innocent" in a western context, not in the context used by militant Islam).

If we want to prevent a terrorist act from occurring in the first place, that means that there will be a lot less evidence, by definition. That is where the trouble begins - going to trial (in court

and in the media, unfortunately) without gunshot residue on the suspect's hands, so to speak. Instead, the evidence is about

possession and conspiracy - which often is not nearly as damning as the aforementioned gunshot residue or, now, DNA is to a general public 'trained' by the CSI television series. But prosecutions based on possession are not a first, by any means - for instance you can't carry a set of lock-picks in the USA unless you are a locksmith (or law enforcement officer trained as such, loosely speaking) or possess child pornography. However, conspiracy is a difficult thing to prove in a court of law; it often looks less convincing to the public, and it gives the defense and its supporters more room to raise doubts about the quality or integrity of the evidence (which is their right, under western-style legal systems). On the other hand, it does increase the chances that an innocent person might be caught up in the web of conspiracy; in the cases where errors may creep in, we trust our system of checks and balances in the judicial process to catch most, if not all, of those. (It is not feasible to implement a "perfect" system, but we do want to get as close to that as practical).

But what else can we do? If we go the intelligence-led disruption route (i.e. we do not try to prosecute and instead focus even earlier in the "chain" on disrupting the cells, networks, and plans in their formative stages), there is even less forensic evidence that will stand up in court. Now we are talking about association, membership, or being a possible threat to the community. That brings with it even more problems than prosecuting cases based on conspiracy and possession. What does the government do then? Deport the suspected terrorist? To where? Most of the places they come from give the civil rights activists apoplexy at the thought of sending them back, but likewise the activists are against detaining them indefinitely instead. I got acousted on the street not long ago by just such an activist, who insisted that detained terrorists who could not be convicted in a western court of law should be released back into the local community at large. My response was to suggest that was a fine idea, as long as he would agree to take them into his own home first.

Now, notwithstanding my attempt at wit, I believe in and respect civil rights and due process. However, I do think it is disingenuous for political activists to ignore the complicated issues involved in disruption operations and the inherent tradeoffs involved. It is just not a serious proposition to release all suspected terrorists - not if they are still considered dangerous by reasonable, informed people - even if it can not be proven in a court of law. What will the public say, and what will the moral culpability of a government be, if they go on to commit acts of violence? "You knew that they could be a

danger to the community and you

released them?!"

This is probably the right point to note that as a practical matter, we can not simply "eliminate the causes of terrorism", no matter how ideal a solution that may sound like. The lessons of history teach that there will always be someone out there who will take offense at the slightest provocation (intentional or not) to use it as a justification for their actions. If you combine that with Islamist beliefs about the Houses of Islam and War, including the return of all lands formerly under Islam to its dominion, and western decadence, it appears impossible to eliminate the causes of Islamic terrorism through negotiation or appeasement.

Some of the grey-haired wisemen say that the only strategy that will work is a combination of prosecution, where possible, and disruption, where not, to keep things damped down (and thereby minimize the loss of life and limb) until this generation of "militants" grows old enough to mellow out. That may be a pessimistic, alarmist, or overly geo-political observation, but it seems true nonetheless.

Getting back on my earlier train of thought, what does all this mean for forensic evidence? Well, there are some patterns in how forensics has changed in the last several years - computer forensics has become increasingly important, for one thing. Why? Others have said that, besides computers' obvious increasing penetration into every facet of western life, it is because computers are a medium of choice for communication amongst the members of the terrorist networks, their support networks, and religious/political base. So, forensic examiners will go where the evidence is. Expect to hear much more about computer forensics over the coming years, but also expect audio and video forensics to continue to play important roles, even if they aren't the flavour of the day, so to speak. After all, seeing and/or hearing the suspect implicating himself or caught in the act, such as through video-taped last-will-and-testaments and security camera images, is no less convincing evidence today than it was before computers.

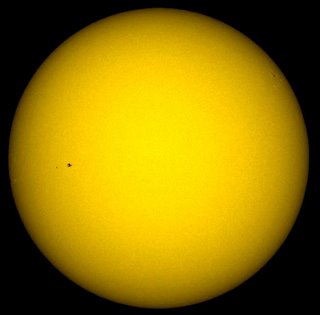

This picture will probaby be all over the Internet soon, but I still think it is worth blogging about here. A French astrophotographer named Thierry Legault took this image using a (serious) hobbyist-grade, ground-based telescope with digital camera attached. We've all been spoiled, maybe even jaded, by the Hubble Space Telescope images in recent years, so it is nice to see Earth-bound telescopes accomplishing amazing things as well. This version is reduced in size, but if you follow the article link (below), you can see an enlarged version that lets you see the Space Shuttle Atlantis and the International Space Station (ISS) against the Sun. It really gives one pause to consider the relative sizes of the objects considering that they are some 93 million miles (150 million km) apart!

This picture will probaby be all over the Internet soon, but I still think it is worth blogging about here. A French astrophotographer named Thierry Legault took this image using a (serious) hobbyist-grade, ground-based telescope with digital camera attached. We've all been spoiled, maybe even jaded, by the Hubble Space Telescope images in recent years, so it is nice to see Earth-bound telescopes accomplishing amazing things as well. This version is reduced in size, but if you follow the article link (below), you can see an enlarged version that lets you see the Space Shuttle Atlantis and the International Space Station (ISS) against the Sun. It really gives one pause to consider the relative sizes of the objects considering that they are some 93 million miles (150 million km) apart!